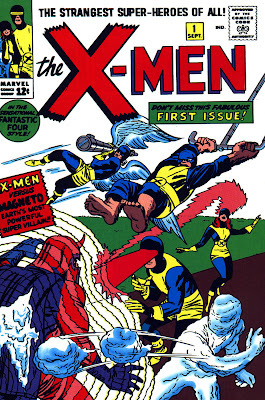

"Don't miss this fabulous 1st issue!"

"In the sensational Fantastic Four style!"

"The strangest super-heroes of all!"

X-Men #1, by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, was cover-dated September 1963. The book started off on a bimonthly schedule. Lee would stay on writing duties for nineteen issues, the last of which was cover-dated April 1966. Kirby penciled only eleven of them, and did the layouts for several issues as well before disappearing completely with #17. Seven of the eight remaining issues were drawn by Jay Gavin (Werner Roth). The art was competent throughout, never outstanding. I won't have much more to say about it.

The original team consisted of Angel, Beast, Cyclops, Iceman and Marvel Girl – mentored by Professor X. Of course, a few things were different back then. Beast was just a guy with big hands and feet, and it would be a long time before he would turn blue and furry. Iceman looked like a snowman in some very silly boots. The team wore their not-quite-iconic blue/black-and-yellow uniforms that would go on to make several returns through the decades.

Lee's run saw the introduction of many enduring elements. Cerebro (originally a very non-telepathic alarm system) and the Danger Room made their first appearances here, and the X-Men were established as operating out of Xavier's School for Gifted Youngsters, though its exact location in the New York area wasn't specified yet. Various familiar villains also popped up, some of whom, like Magneto, Juggernaut and the Sentinels, would go on to play important roles in the books.

Now, this was Stan the Man at the top of his game. Around the same time as he left X-Men, he and Steve Ditko had just completed the incredible Master Planner saga in Amazing Spider-Man. Shortly afterwards, over in Fantastic Four, he and Kirby were starting a little something called the Galactus Trilogy. In short, while the Marvel Age had started with a bang, it was only getting better.

But despite the creators' chain of successes, X-Men never really took off. It wasn't an abject failure, or it would obviously been canceled, but it was never anything more than a cult favorite either. Both creators left early on. Owing to some no less talented successors, the title stuck around for quite a while... until issue 67, when it was reduced to putting out reprints. But we'll get to that soon.

So what went wrong with the X-Men?

Well, for one thing, the characters paled in comparison to other Marvel ensemble casts of the time. In the case of the Avengers, the team was composed of previously existing heroes whose personalities had been defined earlier, in their own books. This meant that each of them had a strong, established identity that didn't get drowned out among other characters. The Fantastic Four, meanwhile, had four main characters as opposed to the X-Men's six. This already would have made them easier to write. Even better, their personalities were based on iconically simple concepts that were yet easy to expand upon: the genius, the young hothead, the tough guy, and the girl. Reading the F4, you got the impression that you were getting glimpses into the lives of real people.

The X-Men, in comparison, seemed much more poorly developed right from the start. It wasn't so much that they lacked personalities, but that these tended to get lost in the shuffle and ended up coming off as vague and unclear. (Part of the problem was certainly the fact that the series spent so little time focusing on the personal lives of the X-Men, thus making it much more difficult for the characters to find individual voices.) Relationships within the team are also pretty unexciting overall. The Marvel revolution was defined by interpersonal conflict and squabbles, and while the X-Men certainly bicker, and often even come to fight using their mutant powers, it's all very mechanical. It comes across as phoned in. In the Fantastic Four, the team's squabbles were all very genuine results of their clashing personalities. Here, there's conflict only because there HAS to be conflict, because it's part of the business model. It doesn't work nearly as well.

Angel is quickly established to be the foppish playboy, but this is only demonstrated in one or two scenes and fails to come across as convincing characterization. Iceman has a very generic impetuous and quipping persona, almost indistinguishable from the Human Torch's. He does have a personal source of conflict – being the youngest of the team – but this is underplayed and ultimately irrelevant. Poor Marvel Girl definitely got the short end of the stick. She has next to no personality aside from general femininity and exists pretty much solely to be pined after by the other members of the team, especially Scott.

The Beast of the first two issues is almost unrecognizable - boorish and unpleasant, demonstrating none of the intelligence and wit that we would come to associate with him. In issue three, he's already using big words and reading books on advanced calculus. In issue eight, his ingenuity becomes instrumental in defeating Unus. Not a case of character development, but of character evolution. The same story also featured him quitting and rejoining the team because he couldn't stand their treatment by humans, which came off as more than a little random.

Cyclops (first introduced as "Slim Summers") was perhaps the best developed member of the team. He already demonstrates his infamous "stiffness" at the beginning of the very first issue, by admonishing Hank and Bobby for endangering Professor Xavier. He also showcases something else we'll see from him in years to come – kicking his teammates' asses. (Remember that.) And as early as issue #7, as Xavier takes a leave of absence, Scott gets the opportunity to lead the team by himself. His brief scenes of lonesome responsibility serve as some of the title's few emotional highlights, though he switches to bantering with the others a bit too readily.

Also, it is important to note that while Scott's lack of control over his eyebeams doesn't seem like much of a problem compared to the severity of some later mutations, they were still a milestone – the first mutant power that inconvenienced its owner. Cyclops's worry over the harm his eyes could do set an important precedent for the franchise.

Xavier mostly plays the part of the stern and strict mentor. There wasn't a lot of variety and he's not very interesting when you get down to it, but this distinctive intensity gave him a lot of presence. There are one or two scenes early on (literally one or two) where Xavier is revealed to harbor a secret attraction towards Jean Grey, but this is quickly dropped, presumably because the staff realized how creepy and out of place this was. Even in modern times, I've seen people express relief that this element was removed, but I'm not so sure. I think it could have been kind of interesting. The idea of a teacher having the hots for his student probably wouldn't have survived long in the Silver Age anyway.

In any case, Xavier takes a surprisingly proactive stance early on. He steps in to help the team several times. He defeats the Vanisher and the Blob, delivers the coup de grace against the Juggernaut and comes up with the strategy that brings down the Sentinels. He's almost too powerful, and I wonder if that's connected to his brief absence from the series. It's hard to say whether he was meant to be written out, and then perhaps brought back because of fan demand.

It's worth noting that, compared to most other major Silver Age Marvel heroes, who gathered their core rogues galleries early on in the sixties, the X-Men picked up disproportionately many of their big villains throughout their later histories. Does this mean anything? Maybe, maybe not. In any case, this was the period where iconic mainstays like the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants, Juggernaut and the Sentinels were born, as well as recurring baddies like Unus the Untouchable and the Vanisher. Others, like Lucifer and the Stranger, aren't that well known nowadays. You'd expect the being who first crippled Xavier – Lucifer – to have a more lasting importance, but I guess not. Oh, and then there's Magneto, of course.

Now, the Magneto back then was not the Magneto we know today. He rose up from humble origins as a somewhat generic “Muahahaha, I'll take over the world!” kind of supervillain, except with the mandate of mutant supremacy to drive his actions. He was bombastic, evil and one-note. There is an intriguing scene in issue #7 where Mastermind is making threatening advances on the Scarlet Witch. Magneto throws him up against the wall, berates him for making treacherous implications and then declares that he wouldn't let anyone who serves him come to harm. Doesn't that seem like there might have been more to Magneto, even then? Well, no. Issue #18 revealed that he heartlessly marooned Toad on an alien world for no particular reason. (“You brainless, inconsequential clod! This is where one like you belongs!”)

Of course, a character doesn't have to be complex and multi-faceted to be an effective villain. Magneto gets the job done, it's just that he doesn't stand out among other, better examples of similar antagonists. All the same, it's not like Lee didn't know how to write sympathetic bad guys. Scarlet Witch and Quicksilver were just that – unwitting pawns who were only part of the Brotherhood because they felt they had a debt to repay Magneto. Reader response was very positive, and subsequently, the siblings didn't last long as villains and went ahead and joined the Avengers. It was that kind of characterization that later made Magneto one of the greatest villains in comics.

Well, this rant lost cohesion a few hundred words back, didn't it? The bottom line is that the X-Men weren't up to par with other characters at the time.

And equally importantly: the book failed to live up to its concept.

Despite the proclamation on the cover, the X-Men, at this point, aren't really very strange. They're all respectable middle-class youngsters, physically almost indistinguishable from normal humans. Sure, they have some visual quirks in their superhero identities, but these are all pretty much non-issues: Angel's wings have almost no volume and can easily be folded up and hidden underneath normal clothing, Cyclops can substitute his outlandish visor with simple red shades and Iceman can turn his snowy exterior off. That leaves only Beast's large hands and feet. The Fantastic Four were much weirder than that. DC's Doom Patrol, the other strangest superheroes of all, were in a whole other league, downright freakish.

Stan Lee has said that he thought up mutants to avoid having invent all new origins for new characters' powers. Mutation, far from being the powerful storytelling device it could and would be, is just a cop-out, and an uninteresting cop-out. The best origin stories have become strong and compelling parts of superhero mythologies, but the X-Men lacked that.

Furthermore, while multiculturalism became a key issue of the X-Men from the Uncanny revamp onward, the original team consisted exclusively of WASPs, though considering the times, this is not exactly unexpected. I give them props for Xavier being disabled and wheelchair-bound though. Aside from the physical aspect, the X-Men operate like a typical superhero team.

So, considering the team was so gosh-darn normal, it's not surprising that they didn't face much in vein of prosecution. Over the first nineteen issues, there are two, maybe three, cases of the general public showing active dislike of the X-Men. If this is the world that hates and fears them, then it is very poorly demonstrated.

This is why the three-part Sentinel storyline is probably the best of Stan Lee's work on the X-Men. Even aside from the concept of Sentinels (who originally looked like over-sized dolls, the exact opposites of menacing enemies), it gave us the most substantial showcases of racism, of the public actually reacting to the mutants among them. This, incidentally, would have been the perfect chance to introduce mutant civilians, to provide a man on the street point of view to contrast with the X-Men and the evil mutants they fight. It's a missed opportunity, to be sure, but not a ruinous one. The storyline does raise the possibility that the team's greatest foe might not have been Magneto, but ordinary people lashing out.

In any case, the story ends with a fairly irritating Deus Ex Machina – Professor Xavier locates a giant crystal that just happens to deactivate the Sentinels – but the struggle leading up to it was pretty thrilling, leaving two team members hospitalized in the next issue, however briefly. The ending, with Bolivar Trask sacrificing himself to stop his creations and no one ever finding out about this, definitely carried a measure of poignancy with it.

(The Juggernaut two-parter was also quite good, though for completely different reasons. It was a very effective case of build-up. Issue #11's cliffhanger teases the Juggernaur's coming – Cerebro goes off and Xavier declares that “the most powerful, most deadly danger [the X-Men] have ever faced!” is almost upon them. The succeeding issue is composed entirely of the Juggernaut fighting the X-Mansion's defense systems while Xavier provides exposition. Only in issue #13 did Cain Marko and the X-Men finally duke it out for real, and the fight is epic.)

So, now that we have some idea on the matter of “what?”, the question becomes “why?” That's frankly a matter of pure speculation, but there's one easy guess I can make.

X-Men and Daredevil were the last important Marvel books that started in the Silver Age. (The Captain America and Iron Man titles started later on, but the characters had been introduced earlier.) They marked the end of the beginning of the Marvel revolution. Interestingly, both had less than spectacular starts, but ended up properly defined and lifted to greater heights by other people in later eras.

At this time, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby were both incredibly busy men. Lee was distributing a lot of work to his artists with the Marvel method, but he was still writing an unbelievable number of the company's books. X-Men was one of his shorter tenures by far. Kirby was putting pen to paper day and night, allowing him to become superhumanly prolific. Both men were swamped. Under this kind of intense workload, perhaps some of the less important titles suffered, perhaps the dream team was just running out of steam. It would have been perfectly understandable.

It's hard to make an overall judgment of Stan Lee's X-Men. Although it was creatively inferior to other titles at the time, nothing about it was horrible – not even especially bad. The worst you could say about it is that it's generic and unimpressive. And yet one of the biggest franchises in comics was born from it. Obviously, there was something there, some kind of feasible foundation. Hopefully, we can work our way onward and take a look at the sheer width and breadth of the material built on these 19 issues.

Index of Happenings:

Deaths: 0.

Resurrections: 0.

X-Men: six (I'm not counting Mimic).

Next time: we'll be taking a look at Roy Thomas's first stint on the title, X-Men #20-43.

No comments:

Post a Comment